Access to the water.

Published on May 13, 2020

“Believe me, my young friend, there is nothing — absolutely nothing — half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats.”

This very famous sentence published in “The wind in the willows” in 1908 summarises all that yachting was in those early days of the 20th century.

A luxury yacht today is mostly a base for all kinds of sports and amusement on the water: Water skiing, riding jet skis, wakeboarding, diving, and more recently several flyboard declinations. The kids are being towed on exotic floating gadgets for a nice speed rush. Tenders are fast and light and used more for enjoyment than just transportation. Very few of those toys have been around for more than a couple of decades.

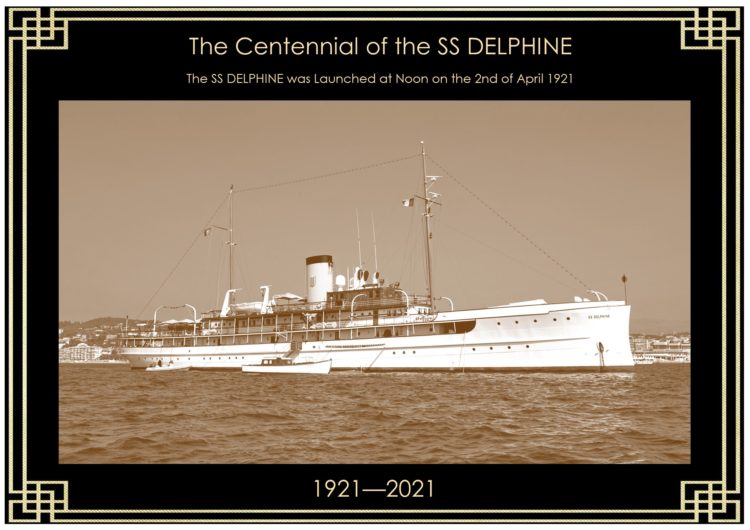

In the heydays of large private yachting before WW2, and before the generalisation of air travel, large yachts were mostly used closer to home. Very wealthy permanent residents of the Mediterranean or Caribbean were few and far between. Yachts had vast expanses of uncovered decks where the owners and friends could enjoy as much as possible of the low sun that the latitudes of Rhode Island or the Solent would scarcely offer. More to the point in this article, the water was cold.

Yachts guests might want to have a short swim, some dinghy sailing or a bit of rowing. More often though, they would have the yacht conveniently close to country clubs to play tennis or golf. They would have parties on board and explore their cruise destination’s sights ashore, very much in the same way as today’s cruise ship passengers do.

The aft tender and bathing platform that is present on most modern yachts started to appear in the eighties. Even then, it was most often added as an afterthought. Yacht sterns retained substantial freeboard to satisfy seaworthiness and load line regulations.

How do we allow decent modern access to water from a classic yacht?

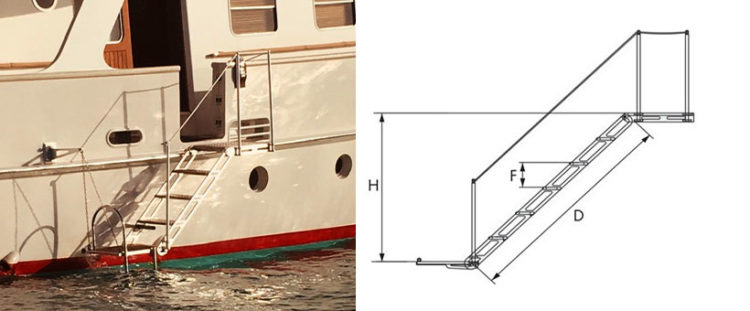

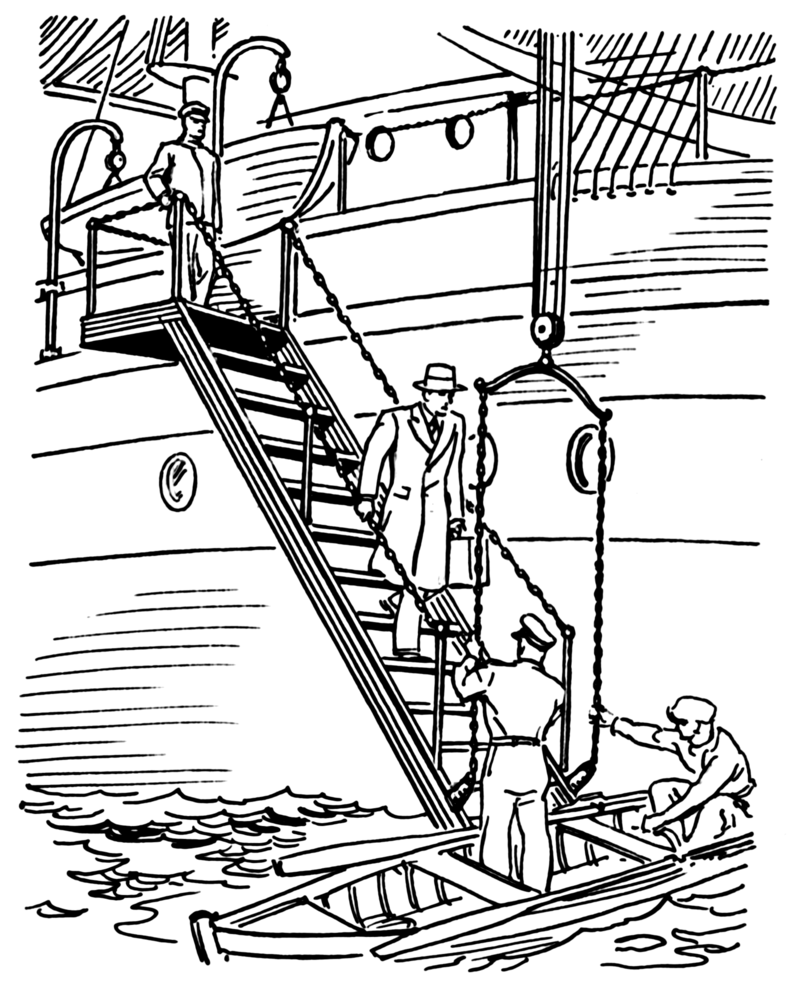

Most classic yachts have accommodation ladders. Those were the traditional way to embark on a tender and often extend to the water if needed. Parking and holding a tender in place while guests safely embark requires good fittings and skills. Some accommodation ladders have an integrated small platform at the foot to make embarkation safer. The ladder or platform can carry or incorporate a bathing ladder to allow swimming around the yacht.

For more space and sturdier access, a side platform can be used. We know of some ungainly side appendages that ruin the aspect of a vessel. A properly designed platform can be closed flush with the hull and be accessible by the accommodation ladder or through a shell door. It can even be the opening for a side garage. Here again, load line rules come in play and the architects must prove the safety of the design.

The main problem with side access is when there is a swell (which is pretty much all the time in some areas). Swimmers must be careful not to get caught in the ladder or under the platform. Furthermore, waves slamming on the underside of a platform can cause damage. A yacht using side platforms should best have thrusters allowing to create a substantial lee on the vessel, even when anchored.

Ships with a high enough freeboard and an overhang, large transom or counter can be fitted with a stern platform. The same can be done for a vessel that has a classic cruiser stern. If the freeboard is lower, a transformer style platform can be designed within the classic shape of the taffrail.

Whenever a platform is fitted, its height is critical. Too low, it will suffer slamming. Too high, it will create problems with tenders and risk for swimmers and toys. Mooring arrangements for tenders and toys should be independent from the platform allowing it to be at least partly raised between uses.

As to beach club arrangements, the ideal solution is probably an inflatable pontoon fastened to the yacht side or even tied to the stern. Some classic inspired yachts, however, have been provided with gorgeous side openings containing a spa and beach club.